Pharaoh Ramesses II

The analysis of the Pharaoh Ramesses II

The mummy was examined in 1886 by Gaston Maspero and Dr. Fouquet, first thorough investigation of the mummy. The investigations were carried out with the means of the time: detailed observation of the body, various measurements.

In 1974, to determine the causes of death of Ramesses II and other mummies, including that of Merneptah, investigations were undertaken under the direction of Maurice Bucaille with Egyptian colleagues and a dozen other French collaborators in various medical disciplines. The results were communicated among others, the Academy of Medicine and the French Society of Legal Medicine. His book The Mummies of the Pharaohs and medicine presents the final results of his research.

Many modern techniques were used, radiological and endoscopic explorations, investigations in the dental field, microscopic research, forensic, etc. A find of great importance due to the use of X-ray films of high sensitivity allowed to show the existence of a very serious injury to the jaw of Ramses II, extensive osteomyelitis of the lower jaw of dental origin. Maurice Bucaille concludes that these injuries were probably fatal condition that the king did not have other undetected serious diseases (due to the inability to examine the chest organs associated with mummification) and that could be the pharaoh who pursued Moses and the Hebrews, for he died in frightful suffering resulting total physical disability.

A study of the mummy of Ramesses II, the Museum of Man in Paris in 1976, concluded that the pharaoh was a “leucoderma, Mediterranean type similar to that of North African Amazigh”.

Pharaoh Ramesses II (of the 19th Dynasty), is generally considered to be the most powerful and influential King that ever reigned in Egypt. He is one of the few rulers who has earned the epithet “the Great”. Subsequently, his racial origins are of extreme interest.

In 1975, the Egyptian government allowed the French to take Ramesses’ mummy to Paris for conservation work. Numerous other tests were performed, to determine Ramesses’ precise racial affinities, largely because the Senegalese scholar Cheikh Anta Diop, was claiming at the time that Ramesses was black. Once the work had been completed, the mummy was returned in a hermetically sealed casket, and it has remained largely hidden from public view ever since, concealed in the bowels of the Cairo Museum. The results of the study were published in a lavishly illustrated work, which was edited by L. Balout, C. Roubet and C. Desroches-Noblecourt, and was titled La Momie de Ramsès II: Contribution Scientifique à l’Égyptologie (1985).

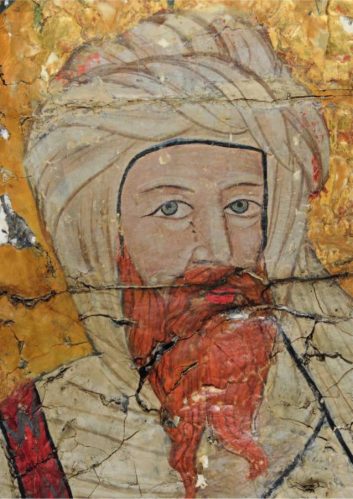

Professor P. F. Ceccaldi, with a research team behind him, studied some hairs which were removed from the mummy’s scalp. Ramesses II was 90 years-old when he died, and his hair had turned white. Ceccaldi determined that the reddish-yellow colour of the mummy’s hair had been brought about by its being dyed with a dilute henna solution; it proved to be an example of the cosmetic attentions of the embalmers. However, traces of the hair’s original colour (in youth), remain in the roots, even into advanced old age. Microscopic examinations proved that the hair roots contained traces of natural red pigments, and that therefore, during his youth, Ramesses II had been red-haired. It was concluded that these red pigments did not result from the hair somehow fading, or otherwise altering post-mortem,but did indeed represent Ramesses’ natural hair colour. Ceccaldi also studied a cross-section of the hairs, and he determined from their oval shape, that Ramesses had been “cymotrich” (wavy-haired). Finally, he stated that such a combination of features showed that Ramesses had been a “leucoderm” (white-skinned person). [Balout, et al. (1985) 254-257.]

Balout and Roubet were under no illusions as to the significance of this discovery, and they concluded as follows:

“After having achieved this immense work, an important scientific conclusion remains to be drawn: the anthropological study and the microscopic analysis of hair, carried out by four laboratories: Judiciary Medecine (Professor Ceccaldi), Société L’Oréal, Atomic Energy Commission, and Institut Textile de France showed that Ramses II was a ‘leucoderm’, that is a fair-skinned man, near to the Prehistoric and Antiquity Mediterraneans, or briefly, of the Berber of Africa.” [Balout, et al. (1985) 383.]

It is interesting to note the link to the North African Berbers: some Berber tribes, such as the Riffians of the Atlas Mountains, have incidences of blondism reaching almost 60%, and they have a percentage of red-haired people which is comparable to that of the Irish. [Coon & Hunt (1966) 116-117.]

These facts have not only anthropological interest however, but also great symbolic importance. In ancient Egypt, the god Seth was said to have been red-haired, and redheads were claimed to have worshipped the god devoutly. [Wainwright (1938) 31, 33, 53.] In the Ramesses study cited above, the Egyptologist Desroches-Noblecourt wrote an essay, in which she discussed the importance of Ramesses’ rufous condition. She noted that the Ramessides (the family of Ramesses II), were devoted to Seth, with several bearing the name Seti, which means “beloved of Seth”. She concluded that the Ramessides believed themselves to be divine descendants of Seth, with their red hair as proof of their lineage; they may even have used this peculiar physical feature to propel themselves out of obscurity, and onto the throne of the Pharaohs. Desroches-Noblecourt also speculated that Ramesses II may well have been descended from a long line of redheads. [Balout, et al. (1985) 388-391.]

Her speculations have been proved correct: Dr. Joann Fletcher, a consultant to the British Bioanthropology Foundation, has proved that Seti I (the father of Ramesses II), had red hair. [Parks (2000).] It has also been demonstrated that the mummy of Pharaoh Siptah (a great-grandson of Ramesses II), has red hair. [Partridge (1994) 169.]

We may also note the anthropological description of Ramesses’ mummy, which was written by the Biblical historian Archibald Sayce:

“The Nineteenth Dynasty to which Ramses II, the oppressor of the Israelites, belonged, is distinguished by its marked dolichocephalism of long-headedness. His mummy shows an index of 74, while the face is an oval with an index of 103. The nose is prominent, but leptorrhine and aquiline, and the jaws are orthognathous. The chin is broad, the neck long, like the fingers and nails. The great king seems to have had red hair.” [Sayce (1925) 136.]

All of these features are characteristics of the Nordic race. [Günther (1927) 10-23.] Finally, we should note that Professor Raymond Dart declared that the Nordic race was the “Egyptian Pharaonic type”. He then went on to state specifically, that the head of Ramesses II is “pelasgic ellipsoidal or Nordic” in type. [Dart (1939).]

By Helen Hagan

Dr. Hawass traveled to the

Oasis of Barhaya, located 200

kilometers west of Alexandria,

and visited Siwa, the Amazigh

(Berber) oasis south of Barhaya.

During the narration of his

journey to the two oases, Dr.

Zahi Hawass did not once mention

the ethnic population of this

desert area, be it now or at the

time the burials occurred (200

BC to 100 AD). When he

mentioned the small local temple

dedicated to Alexander the

Great near the Oasis of Barhaya,

he did state that Alexander

briefly voyaged from Alexandria

to the region. Surprisingly, Dr.

Hawass omitted to provide the

reasons and the extent of

Alexander’s journey. However,

the historical record is clear:

Alexander the Great only traversed

the region of Barhaya on

his way to the oasis of Siwa,

because he needed to reach the

source of legitimacy in Egypt,

where the first priesthood of the

central God of Egypt, Amon, is

said to have originated. He

needed to be empowered by the

Issiwann, spiritual guardians to

early Egyptian religious traditions.

The Greeks called the

inhabitants of the Oasis of Siwa

“Ammonioi”, and the locality

“Ammon.” The God Ammon

was the equivalent to Zeus in

Greek mythology or Jupiter in

the Roman pantheon of Gods.

Dr. Hawass not only omitted

these details, but he spoke

of traveling himself to the Oasis

of Siwa without indicating the

reason for his interest in it. Siwa

people are an Amazigh (Berber)

speaking group. In fact, the

whole region of this desert of

Western Egypt is known to

scholars for being Libyco-

Berber territory.

The field of mummies found

by Dr. Hawass is located near

the ruins of a fort dating back to

Roman occupation, which occurred

after the defeat of

Cleopatra and followed the

Greek colonization of the area.

The Greek Ptolemaic Dynasty

which was inaugurated by

Alexander the Great reigned in

Egypt from 600 BC to 200 BC

at Alexandria, and the Roman

colonization in the vicinity of

Alexandria lasted from that time

to about 100 AD. The dating

of this giant cemetery, tentatively

thought to cover four

square miles of desert, and

possibly holding the remains of

bodies, seem to span several

centuries over the Greco-

Roman period.

The slide pictures were impressive.

Some showed the gold

masks of the deceased that had

been sculpted from their actual

features. However, slide after

slide, it became apparent that

these deceased people were all

light-skinned, full-lipped,

straight-nosed, neither Nubians

nor Sudanese, not copperskinned,

not Asiatic, but indeed

Libyans, that is to say, Amazigh.

The Greeks and Romans who

colonized them collectively

called the Amazigh “Barbaroi”

or “Berbers”. The only mummy

removed and transported out of

the area for the purpose of tests

was an unnamed individual

wrapped in brown resin-coated

bandlets, who Dr. Hawass has

nicknamed “Mr. X.” It was

learned that Mr. X would be

properly reburied after his return

to the area.

When the floor was opened

to questions, I requested from

Dr. Hawass additional information

about the ethnicity of the

people of Barhaya. Dr. Hawass

said that they were “Egyptians.”

When I suggested that in 200

BC, in the desert west of

Alexandria, the indigenous

populations were Libyco-

Berbers or Amazigh, like the

population of the Oasis of Siwa

today, Dr. Hawass was very

quick to assert that he had said

“Egyptians”. He added that

these people looked like me. He

continued in haste to add they

looked like himself and that their

origin was no other than

Egyptian. To conclude his

commentary, he indicated the

following: “I know nothing

about the people you mentioned.”

Later, during a private conversation

with him, I inquired

about any documentation or

historical record, Roman or

other, on the existence of this

Roman fort that had been

erected near a substantial local

population of Libyans (which he

had estimated at being well into

the hundreds of thousands over

time). Dr. Hawass categorically

denied the existence of any such

records. “Nothing is known of

this population in the annals of

history,” he essentially repeated,

asserting that these mummies

are of an undefined origin. He

added that these mummies were

of no particular ethnic origin and

that there were simply Egyptians

and definitely no Roman or

Greek. He also mentioned that

some of them them appeared to

be fairly wealthy, and might have

been artisans or involved in a

thriving wine-making community.

Dr. Empereur, in a later

private conversation, corroborated

my tentative hypothesis

about the ethnic origin of these

mummies, by saying that it is

most likely that the Bahraya

people were Berber or Amazigh.

He also indicated that he was

familiar with French linguistic

research, which places populations

of Berber speakers

throughout Libya, the Oasis of

Siwa and the whole western

desert of Egypt. “It is therefore

justifiable,” he said, “to state

that these burials are of Berber

people. They most likely are.”

When questioned on Dr.

Hawass’s evasive position, Dr.

Empereur readily admitted that

we were talking about “Colonial

Archaeology.”

Indeed, such was precisely

the point, and Dr. Hawass, as a

scientist, had quickly evaded the

issue of indigenous burials in

front of an audience of two

hundred people. He also

publicly stated his lack of

knowledge of the origins of such

burials, to avoid the cultural and

political repercussions that such

recognition would entail. This

evasion raises the question of

scholarly probity, and historical

truth, not to mention the rights

of disposal of these sites, a

political question of no small

dimension.

When I shared some of my

concerns with Amazigh

(Berber) people through a quick

internet note, Dr. Hassan

Ouzzate, Associate Professor,

Faculty of Letters and

Humanities at Ibn Zohr

University of Agadir, Morocco

provided the following comments:

“…Egypt is particularly

bad in this domain… Egyptian

historical vestiges are there to

belie such an attempt. What

happens is a very selective account

of truth. Official historical

accounts have always considered

any cultural influence coming

from “west” of the Nile (The

Land of the Dead) as nefarious

to a mythical central Egypt…

The name of the group you

mentioned (Bahraya) attracted

my attention as a possible

Amazigh form for the following

three reasons:

1. It is a collective name for the

people, not a geographic

name. Why? Because it is

the usual Arabicized plural

form given to a great many

tribal names throughout

North Africa. Examples:

Gzennaya, Schawiyya, and

Ghardaya.

2 One can easily return the

form to its original

Amazigh: Igzenayn,

Iccawn, Igherdayn,

Iberiyyen…

3. It is clear that the derivation

is from “BHR” (or Arabic

‘BHARI”) meaning “of the

sea”… Therefore “abehri”

(pl. ibehriyn) is a perfectly

good Amazigh term, denoting

the “people of the sea,”

whether that means “by the

sea” or “from the sea” or

“living off the sea”. Notice

that if the power of naming

resided with the Siwa

Oasis, an agricultural, sedentary

and inland group, the

appellation would be very

logical.”

In addition, I consulted the

published research of

Mohammed Chafik, member of

the Moroccan Royal Academy,

on the topic of the prehistoric

origins of the Egyptian pyramids.

The work includes specific

information on the Oasis of

Siwa, the travels of Alexander

the Great in the area, and the

common linguistic origins of

Berber and Egyptian burial complexes.

It is from Mohammed

Chafik’s work that I learned of

Alexander’s visit to Siwa, and

became familiar with the Arabic

poem that he quoted. Dr. Chafik

notes that the journey of

Alexander the Great to that

oasis must have been of great

importance to the antique world,

for ten centuries after it occurred.

The poet Umayya Ibn

Abl es-Salt related Alexander’s

journey: “He (Alexander)

reached the West, seeking from

the Guides of Wisdom some

foundations for his power. So he

went, in the direction of the

setting sun, where, at evening,

the sun sets near a source of

bubbling waters.” There are

well-known bubbling wells of

salt water in the region, more

than two hundred in the Oasis

of Siwa.

Dr. Chafik concluded his

remarks on the ancient sanctity

of this region of Amazigh culture

with the following comments:

“Though experts are still

debating which one of the two

temples of Ammon, that of

Thebes or that of Siwa, was

founded before the other, all

indications point to the anteriority

and the primacy of the oasis

complex of the Libyan desert.”

(Tifinagh: Revue de Culture et

de Civilisation Nord-Africaines,

August 1997).

In conclusion, it is my

opinion that once again in a long

series of historical misdeeds and

cultural distortion, the scientific

world is about to be tarnished

by committing another form of

violence to history. This

violence results from the shortsightedness

of Egyptian scholars

and an Egyptian leadership,

which might be afraid to respect

the truth for political reasons. In

Egypt, it is more politically

correct to declare all finds

“Egyptians” and to refuse to

discuss the ethnic origins of this

find. However, it is ethically

incorrect and deplorable to deny

the international community the

truth of history in the name of

nationalism and the protection

of Middle Eastern interests in

Africa.

A cultural treasure is about

to be plundered once again.

This time, it is the case of the

refusal of Egyptian scholars and

the Egyptian government to address

the Amazigh origin of the

archaeological treasure. The

audience was misled into thinking

that the newly discovered

field of Golden Mummies covering

a large portion of the western

desert of Egypt are human

remains of undetermined origin ….

Also read the publication on the same theme.

https://mergueze.info/thor-heyerdahl-discovering-great-civilizations/